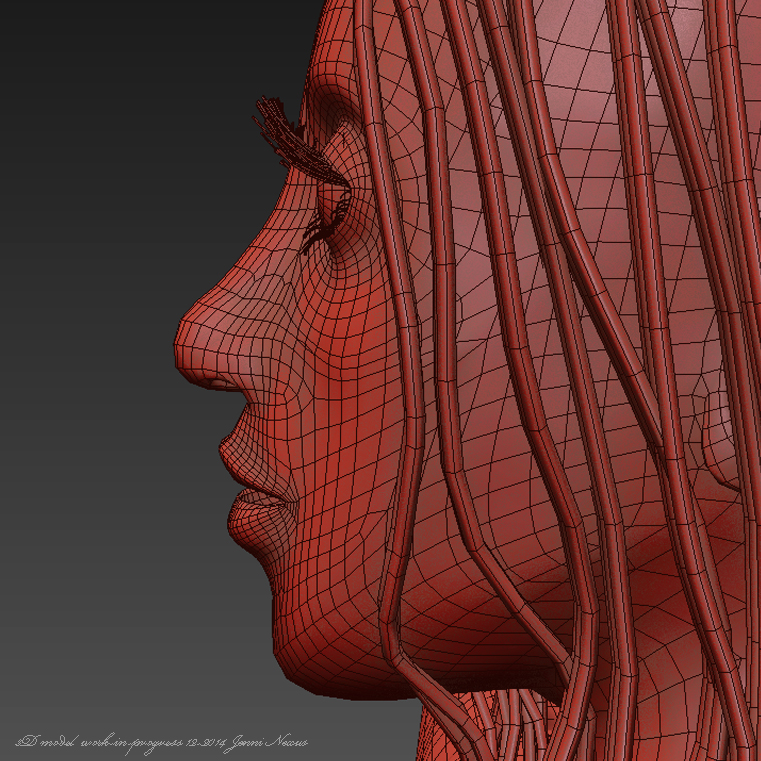

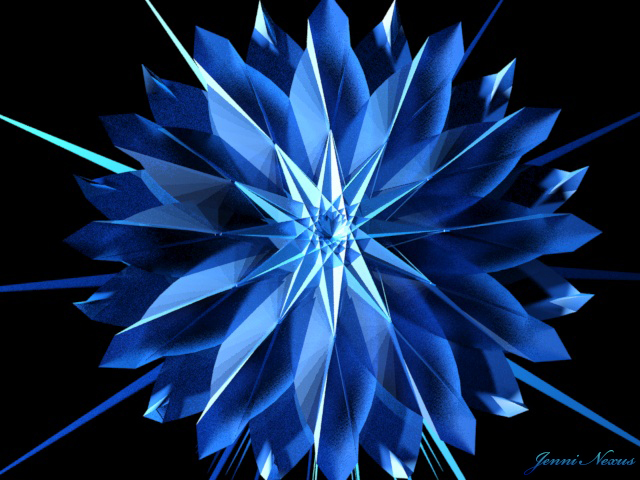

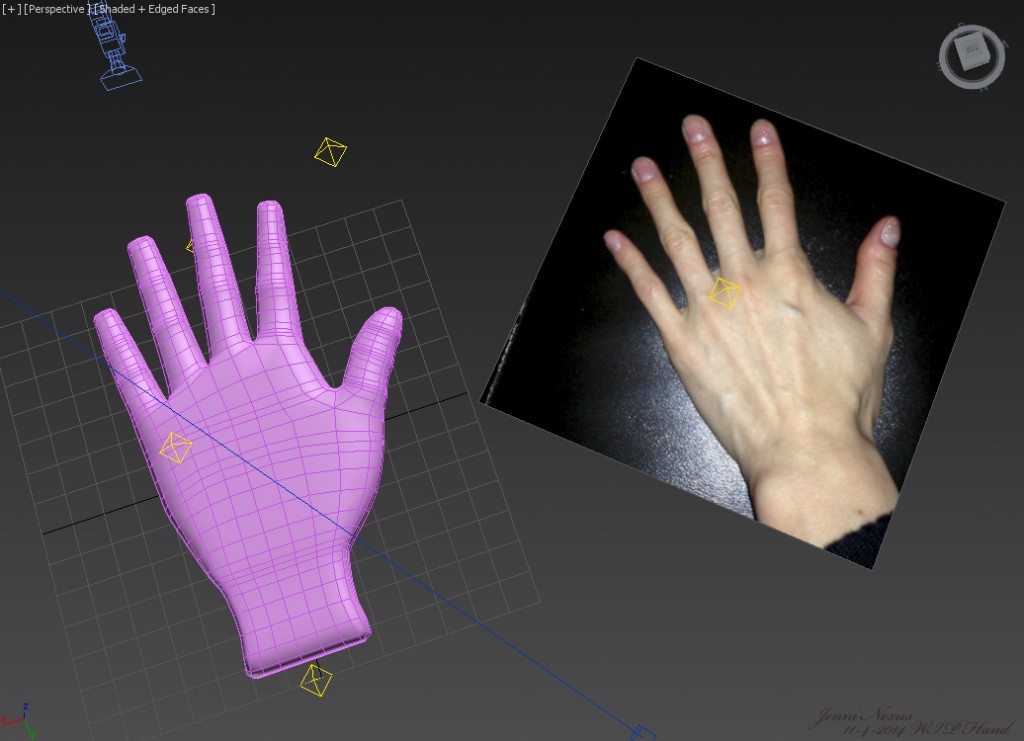

Poetry by Walter Bargen ÷ Art by Jenni Nexus

List Beyond the Stars

Haven’t seen a snake in months.

No scream necessary unless

the thought itself

slithers across your forehead

flicking its forked tongue.

No wet rip of flesh stretched

across asphalt as the car tires

zip past. Just the hum of tread

measuring empty miles.

It’s the same with turtles.

Highways empty of turtle soup.

The crush of dry leaves clawing

a way over forest floor not there.

The oaks dropping leaves

three months early. So much filing to do

and the alphabet missing so many letters.

Not a blunt scaly leg to hire.

Heard only one whip-poor-will this year.

Dozens if not hundred of thousands gone.

To where? The night silence a roar.

When’s the last time a woodpecker

Tapped out its code?

I don’t know what will survive.

I try not to look too closely

anymore. It’s already

possible to count solitary blades of grass.

Laundry Day

I wasn’t looking for gainful employment

But was told to find a clothesline.

Old friends stood around with walleyed stares.

Strangers overflowed with advice:

Under the sea by the pier

Where the fish hangout,

In the trees behind the house

Where the birds perch

With a clothespin stillness,

Never underground–

Too dirty and the rot fits all sizes,

But it’s where I found a telephone

Sleeping with ear plugs.

I answered but no help there.

I started searching along the street

I started searching along the street

Thinking someone might have handcuffed

a few vagrant bushes.

There were warning shouts

That I can’t go beyond the corner,

All the other streets aren’t mine.

So the clothes on my back are wet.

I slosh with each step.

I can’t tell the difference

Between the spin cycle and drowning,

They drip with the same indignation.

. . . because I sometimes feel it may not continue to exist much longer. . .

–Thomas Merton

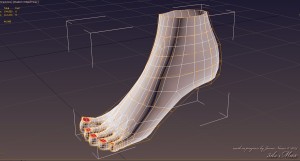

1

He isn’t certain whether cosines

And square roots are needed,

As he sums the cost of an arm and a leg.

Any way he manipulates the figures

With a bit of Dr. Frankenstein,

But the calculator won’t perform

the grisly calculations.

New batteries don’t perk it up.

He goes digging in a closet, pushing aside shoes

that haven’t lodged a foot or complaint

in years. The dust monumental

and guarded by cherubs. The towering

cobwebs the clothes of ghosts.

He finds the box where his army rests,

assembled in his tricycle years.

When he was twelve he resigned

his command of forces who were always on the attack

to become a pacifist. Little rubber figures,

the color of pond scum, forever in the position

of throwing a grenade that surely has exploded

by now, lying prone and aiming, their rifles

surely out of ammunition, crouched and running

and if not blown to smithereens by a firecracker,

then surely severe back pains ensued.

Sure enough at the bottom of this boxed army,

rolling aimlessly around orphaned arms, legs,

hands, and even a couple of heads, the loss making

no difference to the aim and bayonet thrust

of their statuesque devotion.

He arranges the maimed soldiers on his desk,

a line that suggests a horizontal axis, a calculable

destination, the simple cost of an arm and leg,

but not for the headless as most of his neighbors

these days head for the November election.

The cost is too much, it frightens him.

At one moment, he’s standing on a sidewalk

In front of a theater, 1957, the movie marquee

reads Bridge Over the River Kwai,

starring Alec Guinness and William Holden.

Half-century later, he remembers the tune

the starved British POW’s whistled

as they marched off to complete the bridge,

then destroy the bridge, Shakespearean style,

by an escaped prisoner who has returned

and is killed along with the Japanese commandant,

the British officer in charge, and two other commandoes,

not to forget the train filled with Japanese

dignitaries plunging into the gorge.

And there he is, leg missing from the hip down,

and no warning, as if he were one of Remarque’s

German soldiers, who looks over the parapet

of a trench at Verdun, and falls back headless,

or is standing guard and for the briefest moment

is balanced on one leg before being spun around,

neon blood fanning out in a circle around him.

He’s devastated, about to cry, chokes back the sobs

in case John Wayne still has manhood cornered,

but he’s only recalling his mother’s father,

a WWI vet struggling across the muddy farm yard,

his one leg submerged to the ankle as he angrily

wrestled with crutches planted deep in the chicken-shit

muck, or maybe it’s his father’s father,

A sailor who survived a mustard-gas attack,

The details never clear, but it was a later heart attack

shoveling coal for the railroad.

He thinks it’s all an arm and a leg,

and it doesn’t matter, we will get there,

one way or another, whole or in pieces.

Leave a Reply