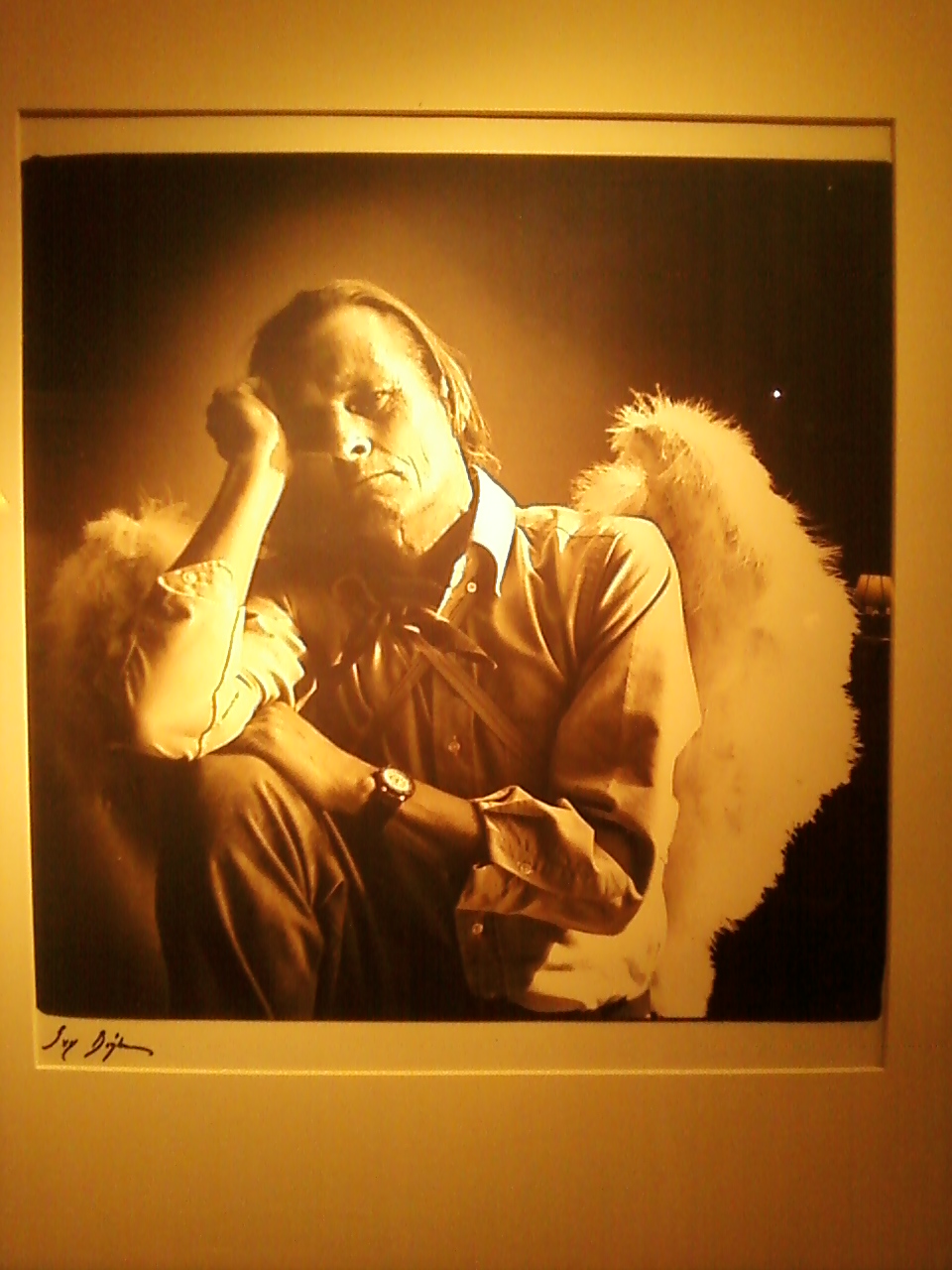

Fiction by Roger D. Hicks, M. Ed Photography of Alan Justiss

The old man finished his breakfast of Cream of Wheat and two eggs on the sideboard of the flour sifter cabinet, placed his plate and coffee cup in the sink and walked out of the kitchen without saying a word to his wife who had eaten with him and prepared an identical breakfast for both. The front door swung shut behind him and he descended the steps slowly. Walking as fast and steadily as his weakened heart would allow, he moved across the yard to the shade of the large white mulberry tree which he had planted more than twenty years before. He had often regretted and denigrated the hundreds of volunteer white mulberries which continually cropped up all over the surrounding five acres but he had never regretted planting this one which had brought on his constant problem with the others.

Slowly, he lowered himself to the seat he had made of two boards along the largest stabilizer root and trunk. The root grew outward from the base of the tree about eight feet before descending into the soft earth of the yard. One board had been nailed to the top of the root and the other had been attached at an angle up the trunk to support his back. The area around the root was scattered with a steadily growing pile of cedar shavings, curled smoothly and slowly from many small chunks of dried cedar from a store of the wood which the man kept hanging in the rafters of his barn high against the overheated tin roof in order to pull the sap and incidental moisture from the fragrant wood to appease his lifelong habit of whittling. The man had, when his health was stable, cut a small cedar tree from his hillside farm every few years, limbed it, peeled the bark, and cut it into small sections in order to hasten the drying process. Every day, when he was able and the weather was hospitable, the man came to the bench on the root and sat whittling, spitting precise, nail like shots of tobacco juice from a chew of Day’s Work, and thinking about his impending death which his doctor had assured him, following his most recent cardiac arrest, was not long off.

“You might last a year if you are lucky, eat exactly what I tell you to, take your medicine exactly as it’s prescribed, and don’t take on any serious physical activity or excitement,” the doctor had said in his best voice rife with the professional detachment he had polished during his years in one of the best medical schools in the world. The old man was trying to eat correctly but he loved eggs, bacon, sausage, ham hocks, brown gravy, fried foods of all kinds, and he hated to be told what to do after having survived the Great Depression and purchasing his own little farm free and clear. He had chosen to weigh the faintly possible reward of a few more months of life deprived of many things he loved against the certainty of the pleasure he could derive from doing just as he pleased and chose the reward he could feel, see, smell, taste, and appreciate in the present. “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,” he whispered to himself as he pulled the well sharpened and well-worn Case knife from his pocket, and reached under the seat for his chunk of cedar. He smiled broadly as the blade sank into the wood and the smell of freshly exposed cedar rose to his nostrils.

Suddenly, he felt a fleeting feeling of loss and pain which had lasted more than fifty years.

The sunrise was just beginning in the east and a warm pink glow rose over the mountains in the distance. Birds were singing and flying randomly about in a search for food for the litters of freshly hatched chicks in the nests over his head. “This mulberry does have one good use, I reckon,” he thought as a female cardinal flew over his head to her nest. The presence of the baby birds above his seat reminded him of the days more than forty years ago when he and the old woman had children and were young enough to remember how they came by them. He thought of the first daughter who had been born almost exactly nine months after they married at eighteen and fifteen. She had played on the dirt floor of that first house they were allowed to live in for raising ten acres of corn on the halves for the man who owned the rocky little farm. Then suddenly, within four years they had three more children and the acre of garden they were allowed to raise when they weren’t hoeing corn just wasn’t sufficient to feed the whole family. He had begun looking for a job in the coal mines and eventually found one and the woman had raised the corn by herself until the children were old enough to pick up a hoe from which he had sawed half the handle. That first girl had used the hoe until her brother, born next, was tall enough to use it. Then she and each of her nine siblings after her had graduated from the short hoe to longer ones and soon they were raising fifteen acres of corn and a two-acre garden of sweet corn, cabbage, green beans, peppers, squash, cushaw, and row after row of potatoes. He had always smiled when he thought about how “it takes a lot of potatoes to raise ten children”. Now he remembered that through it all he had not been unhappy with a small, crowded house and too many children to raise comfortably.

Suddenly, he felt a fleeting feeling of loss and pain which had lasted more than fifty years. He remembered how his second born son had grown into a fine, healthy boy of fifteen, a hard worker, obedient, industrious, devoted to his family, and well on his way to being a fine man of whom a parent could always be proud and had suddenly awoken one morning with an indeterminate “fever” and was dead before the country doctor could be induced to drive his Model A twelve miles from town to the head of the little hollow in which they lived. Nearly simultaneously, he remembered the third born daughter who had awoken one cold November morning at the age of three and while backing up to the hearth to warm herself had swept the tail of her cotton nightgown into the hot coals behind her. His wife, cooking breakfast in the kitchen, heard the child scream and ran to put out the fire in time to have the little girl live three days in immense pain which the same country doctor could do nothing to prevent or stop in spite of the fact that by that time they had saved fifteen dollars all of which they gladly paid the doctor before he even left his house to see the child. These thoughts of loss and failure had come to him repeatedly since he had nailed the two coffins together with hand hewn boards and watched his wife choose each of them one of her better quilts in which to lie in repose for the funeral at the little church where they now lay buried in graves marked only by the same rough boards which had rotted and been lost in a cemetery which not even the old man mowed anymore.

His losses had been horrible, devastating, but not unbearable. Over time, he had learned to accept the deaths of his children. Now, with a pocket knife in his hand and a chew of tobacco in his mouth, he was searching for a way to accept and bear his own impending death. He was struggling both with the simple fact of mortality and the fact that he suspected his death would not be an honorable one by his standards. He had always imagined dying in motion not tied to a house and fifty feet circumference if his frail heart didn’t chain him even closer to his bed. He had often thought of dying while riding a horse and falling quickly from the saddle, or falling off a roof while repairing shingles. He had grown to believe that an honest, hard-working man such as himself should die an honest, hard-working death. This waiting while whittling on the root of a shade tree was not a good way to approach death. Death, in the old man’s mind, should be faced, head on, eye to eye, stared down as long as possible, and accepted only when there was no other alternative. “This ain’t no way to die,” he complained under his breath.

The struggle in his mind never managed to translate itself to his steadily moving hands. The knife kept dancing in smooth, practiced motions up and down the cedar. The shavings kept falling beside the tree root. The old man kept thinking about his life and approaching death, whittled and thought, thought and whittled as the sun began to warm the land around him. The leaves on the neighbor’s corn opened to receive the heat and light and began working to make new chlorophyll and sugary kernels just as the old man had once walked into his fields with a hoe at sunrise to help the corn in its work. He gazed at the neighbor’s fields and wished once again that he had been able to plant a little garden this year. “No man’, he thought, ‘should ever be without a garden big enough to get him through the winter.”

As he whittled and thought of not being able to raise a garden, hoe corn, cut firewood, or live a normal working man’s life, the old man thought also of his failures and successes. He realized that the successes were greater than the failures despite his being distressed by the illness which guaranteed his imminent death. He had raised eight of ten children to productive adulthood. He had managed to survive the Great Depression, the Hoover Days as he remembered them. He had saved enough money to buy this little home place and pay cash for it. He had always been able to keep a milk cow, a plow mule until he sold the last one after the last heart attack, and the tools necessary to make a living for himself and his wife. Every year until this one he had bought, fattened, and butchered a hog. Now, he considered it a personal failure that he could no longer walk the hundred yards to the hog pen which he had attached to the side of his hillside barn in such a way that the manure automatically gravitated over his garden without entailing extra labor to haul and spread it.

As he enumerated his successes, he remembered that the local banker at the county seat in Wide Spot had always told him, “If you ever need to borrow a little money, we would be glad to give you a loan. We know the kind of man you are.” He smiled broadly as he remembered that he had never taken the banker up on that offer. There might have been times when he got by on less than he would have liked but he had never had to borrow money from a bank in his life. His children had never gone hungry either. The knife blade slowed in its motions as he relished that thought. He had always considered being in debt to be a failure. He had also always been respected by the local political figures who always stopped by his house in an election year to request his help in gaining the votes of his extended family. A man with eight adult children and more than two dozen grandchildren could influence a lot of votes if he was respected. The old man knew he was respected.

His whittling became more normal, slow, steady, peaceful, restorative, and the soft smile which usually crossed his face returned as he found peace in the knife and cedar. Then he caught a whiff of wood smoke and thought someone must be burning brush and remembered how hard he and his wife had worked in the first few years of their marriage to clear new ground on the old hillside farm they rented. He remembered cutting brush and small trees with an axe and crosscut saw, dragging the brush to the center of his new field to burn in an area where it would not be likely to catch the mountains on fire. Slowly they had changed that abandoned old farm into a clean place where they had lived until he had worked in the mine long enough to buy an even worse place farther up another hollow which they and the children had also tended, dug, cut, burned, and improved until they could afford to build a small house and finally move onto land which they owned. He was pleased with his life. It was his likely death that kept rearing its ugly head to confuse and frustrate him. He did not relish the thought of dying in a bed even if he was surrounded by his ever expanding family.

Sudden he realized the smell of wood smoke was stronger and looked up the creek to the home of his nearest neighbor where he saw a plume of smoke rising from the back of the house where he knew there was no chimney. He also realized the fire was too close to the house to have been brush or garbage. He yelled to his wife in the house and stood to get a better view. Suddenly, he knew the house was burning and his response was exactly what it would have been if he had been thirty years younger and perfectly healthy. He pocketed the knife, dropped the cedar and began to run up the creek to help fight the fire. His neighbors needed help. He needed to be there.

As the old man ran, his heartbeat accelerated and his breathing became more labored. But he kept running with the same kind of determination that had made him work twelve hours a day in the mines and come home to plow corn by moonlight when he was young. But the continued effort began to take its toll and, without warning, he felt the old, familiar, fatal, tightening in his chest. He knew this was another heart attack and smiled as he kept running until he fell in the edge of the neighbor’s yard. Just as his wife caught up with him and dropped to his side, he managed to smile one last time. This was falling out of the saddle. This was not a death in a bed in a darkened room. This was the way a working man and good neighbor should die. This was honorable. He smiled.

Copyright 2016 by Roger D. Hicks

Leave a Reply