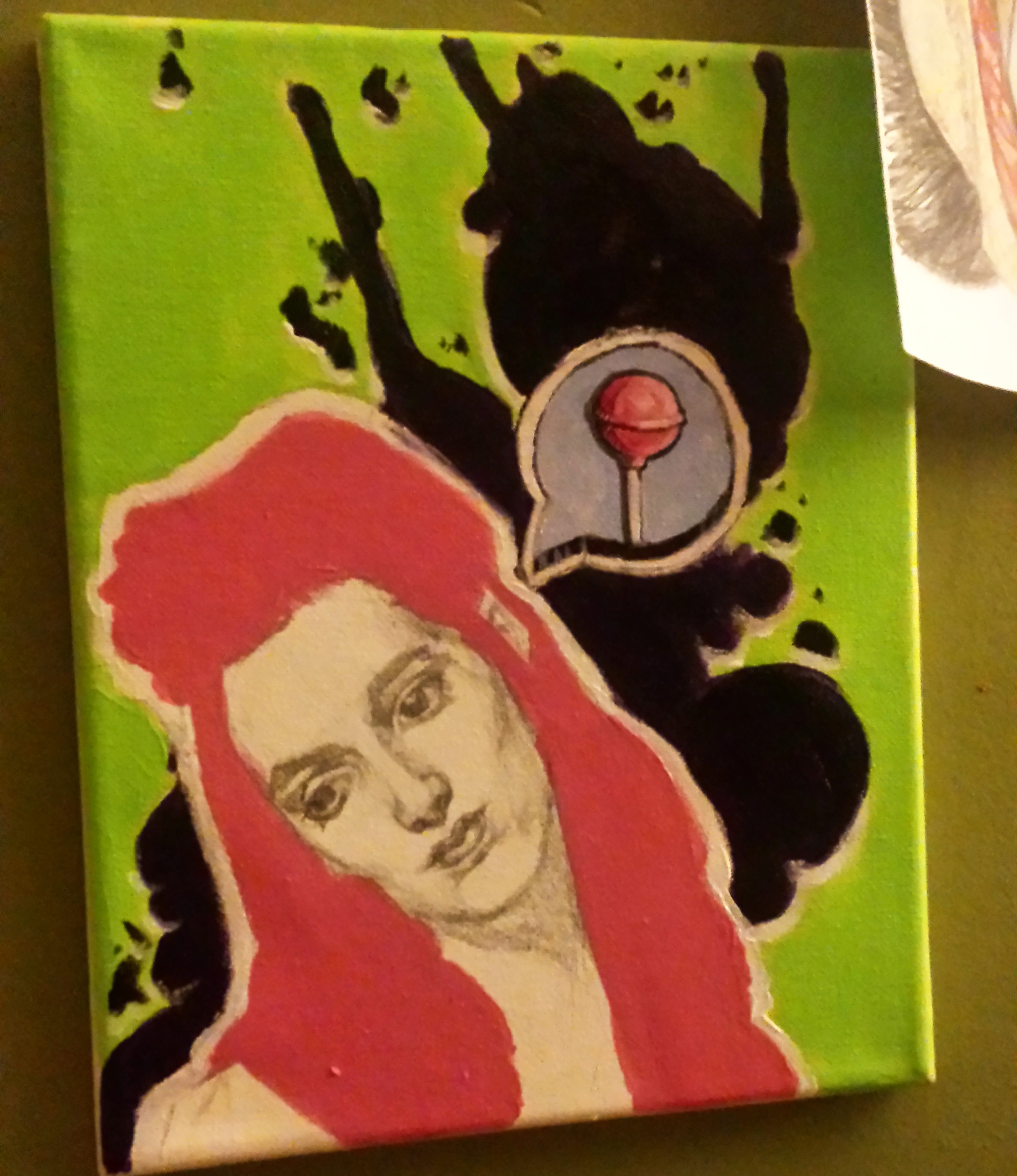

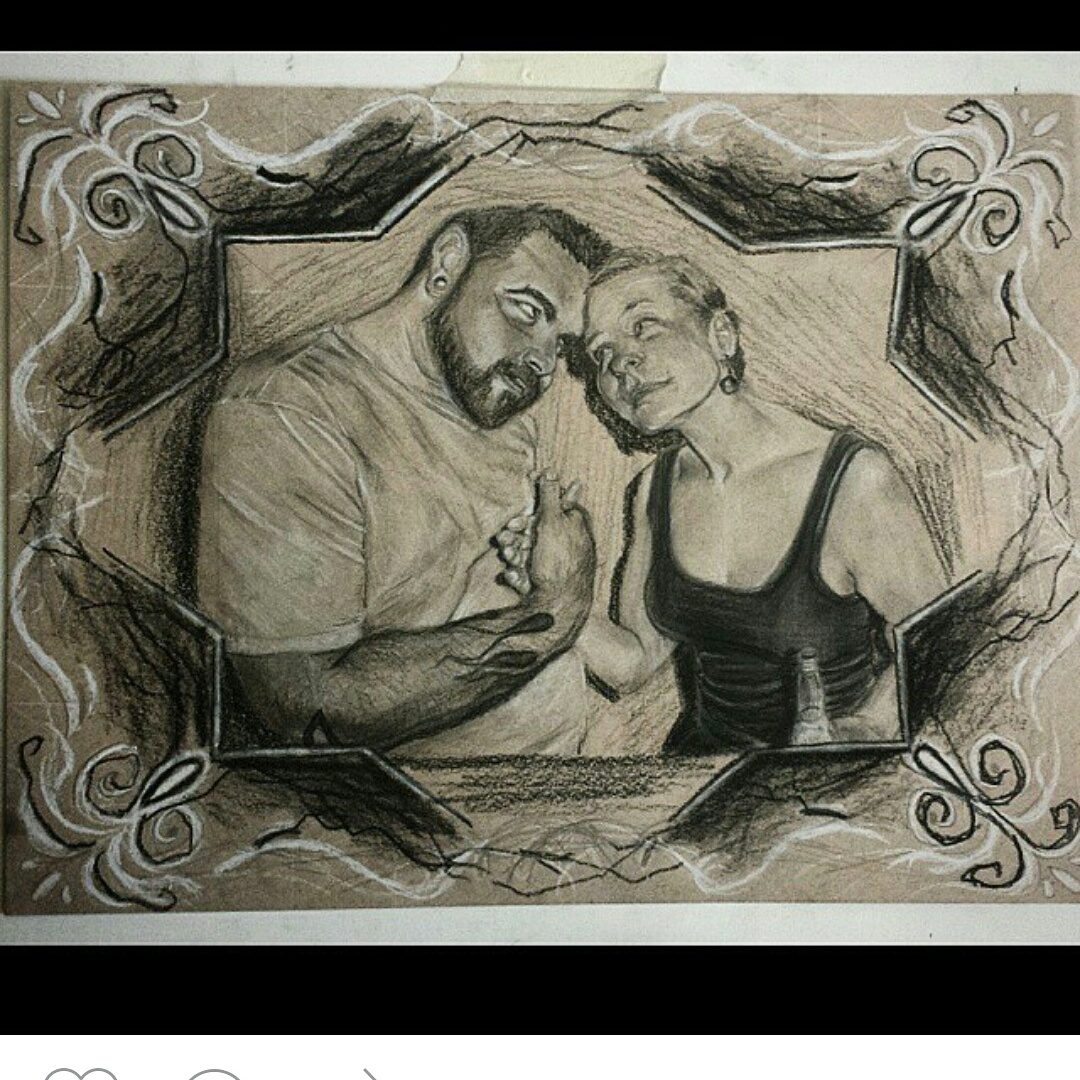

Fiction by Joshua Britton ♠ Art by Mychelle Bentley

Ray sent me a friend request and a message. It said nothing special; he was wondering what I’d been up to all this time. I hadn’t thought of Ray in years and hadn’t seen him in even longer. As children, we lived on the same street. Back then, we didn’t need a better reason to be friends.

If childhood ends with puberty, we were knocking on the door. Matt, Tobin, and I had just lost our best friend after his family moved to the rich side of the city. We were still in mourning when the new kid arrived. This put Ray at a disadvantage from the start. Ray never fared well in comparison to others.

He certainly didn’t make a strong first impression. He was smaller than Matt, Tobin, and me. He spoke with saliva, and he laughed inward, as if it didn’t come natural, he didn’t actually think something was funny, and he was just trying to fit in. He was an odd little runt. And we couldn’t make sense of his Jacksonville Jaguars clothes. They don’t like the Jaguars even in Jacksonville, so why was a kid in upstate New York telling people he rooted for an expansion team?

Ray’s mom and Sal lived together even though they weren’t married. That was unusual. My parents had recently separated but at least they used to be married. And Ray called him Sal, not Dad. Maybe Sal wasn’t Ray’s real dad. I never learned for sure.

Sal yelled. Nobody had air conditioning so windows were always open during the summer. Tobin lived next door to Ray, and from inside Tobin’s house we could heard Sal screaming at Ray. Sometimes we heard a bang or a crash. After those outbursts, his mother answered the door to tell us Ray couldn’t come out to play. Come September, Ray missed time at school.

We were not destined to be lifelong friends, Ray and I, though for a while I ran into him here and there. He made the news when he was a high school senior. After school one afternoon he and a friend were racing to Burger King. Burger King was at the bottom of a hill down a stretch of road where everyone had gotten a speeding ticket at least once. The road narrowed from four lanes to two, which was good news for Ray because he was winning. But the cars in front were slowing down, and for Ray slowing down meant risking the lead. There wasn’t any oncoming traffic, and, because he couldn’t imagine anything worse than pulling in last to Burger King, he changed lanes to pass the slow pokes. The reason for the slowing, however, was that at the front of the line an elderly woman was about to pull into her driveway. She turned left just as Ray tried to pass. To his credit, Ray was wearing a seatbelt, and he suffered minimal injuries when he slammed into the driver’s side of the turning car. The woman didn’t make it. Ray was eighteen, and he did some time.

*

In the mornings, Matt, Tobin, Ray, and I would bid our parents farewell until supper and race out of our neighborhood, across the expressway on-ramp, over cars screaming and eighteen-wheelers roaring underneath the bridge, with a quick stop at the gas station to buy pop and slushies, and down the boulevard a ways before finally veering off to the right into a labyrinth of dirt bike trails. The trails were well-worn and mostly easy to navigate, though in one spot, a log had fallen, leaving only a ten-inch gap to thread bike tires through. After all our practice, only occasionally would anyone wipe out.

A mile in any direction we might’ve been run over by a minivan, but the woods felt like wilderness. There were even fish in the creek. I never saw one more than a couple of inches long, but we tried hooking them anyway. Away from the water there were hills that were great fun to bike down, especially after some bigger kids piled up a dirt mound at the bottom where, going full speed, we could get serious air. And in the winter, the four of us simultaneously raced down on sleds. The objective was to create the greatest sledding collision ever. If someone made it to the bottom of the hill unscathed, he would look back at the mess of sleds, snow, and limbs, and feel sorry for himself.

Unless someone’s parent happened to be going for a run through the woods, we went hours without adult contact. Nobody was ever kidnapped. We swore with the best of them, but we never did drugs or smoked cigarettes. Pretty much everyone suffered bloody noses, bruised ribs, and mild concussions, but nobody died.

What we needed Ray for most was two-on-two football. With only three people, we were limited to Murder the Man With the Ball, which was fun, but not authentic enough. Nobody wanted to be paired with Ray, but Matt, Tobin, and I used a steady and tactless rotation to decide who was stuck with him on any given day.

It was hard having Ray as the only option. Matt, Tobin, and I were pretty evenly matched; I can’t say one of us was better than the other two. But Ray couldn’t catch or throw. He could hand off to someone all right, but handing off to him proved more interesting.

“Ok, Ray, you’re going to line up in the backfield to my left. I’ll yell ‘Hut!’ and you go in motion, cross over to the right. Then it’s ‘Hut! Hike!’ and I’ll pitch the ball to you. You’re the Jaguars’ running back, all right? What’s his name?” Ray looked at me blankly. “Never mind. Anyway, they’ll be following you so cut back towards me immediately. I’ll block the way and you take it in. Ready?”

We broke the huddle and I held the ball out to where I best guessed the line of scrimmage to be. Matt was in front of me, ready to count to five Mississippi before he could blitz. Ray lined up to my left but in front of the ball – off sides.

Tobin was lined up opposite Ray. “I think you gotta back up,” Tobin said.

Ray took a step back.

“More,” I said.

Ray took another step back.

“Back up like ten feet, man,” I said.

Ray was a deer in headlights so I called “time out” to go over the instructions again. This time I blatantly pointed to the spot I wanted him to stand, and to the route I wanted him to run. He appeared to comprehend so I took my position back at the line.

“Hut!” I yelled. Ray didn’t move. “That’s your cue, dude,” I said. Ray jogged to his right, behind me. “Hut! Hike!”

I lateraled the ball back towards Ray. He held out his arms but the ball hit him in the face.

“Fumble!” Tobin yelled.

A loose ball meant Matt and Tobin didn’t need to wait for five Mississippi before crossing the line. Matt was the first to the ball and bent over to pick it up and take it the distance, but his feet got in the way and he booted it out of reach.

“Jump on it, Ray!” I yelled, breaking after the ball behind Matt and Tobin. Ray was quick and had a beat on it. He lunged but his aim was off and the ball squirted inches away. I put my arms up and took out Tobin. It might’ve been an illegal hit, but we were both laughing before we hit the ground.

With Ray on his belly, Matt tried to jump over him to get to the ball, but Ray rose just as Matt was midflight and tripped him. Matt fell on his face while Ray yelped in pain. Tobin and I got up to catch up with them. Ray army-crawled to the ball and got a hand on it just as Matt arrived. Tobin dove through the air, landed on the two bodies, kneeing them both in the back, and pronounced, “I got it!” Not wanting to be left out of the pile-up, I jumped on top.

When we got the ball back, I made Ray quarterback. I didn’t mind taking handoffs, but it got boring, so I told him to throw it up. He had no aim, but if he got the ball high enough, I thought I’d have a decent chance of making a play. The first attempt was remarkably successful, which I guess gave us false hope because Ray’s next two throws somehow went backwards. Tobin pointed out that an incomplete backwards pass was the same as a fumble. I decided not to risk Ray throwing backwards again. I took over at quarterback and stuck the ball square in Ray’s gut. It took him a second to secure the ball, long enough for Matt to meet him in the backfield and take his knees out. We had to punt.

I stuck with the conservative game plan each time we had the ball. Occasionally Ray wriggled away and picked up a couple of yards. Then we slapped fives as if we just won the Super Bowl. More often than not, though, either Matt or Tobin barreled into his chest and drilled him into the ground. One time Ray tried an ill-advised leap into the air, as if he could fly over his would-be tacklers. Matt caught him and, with Ray and the ball in his arms, ran the length of the field for a safety. Tobin brought to our attention the “forward progress” rule, which prevented such defensive plays, but I let the safety stand anyway.

This went on for a good half hour in Tobin’s and Ray’s backyards. Ray never complained. He took handoff after handoff, and big hit after big hit. When he didn’t rise right away, I held out my hand to pull him up. He seemed to like that, and he smiled. Then I gave him the hand-off, and he got leveled again. The score was as lopsided as ever, but it sure was hilarious.

Ray was tackled for roughly the thousandth time that afternoon when we heard Sal crash through the backdoor of their house.

“Get off of him!” he yelled, instantly upon us.

When Sal said something, we listened. His tone of voice was familiar, except we were used to hearing it from a distance. Matt, Tobin, and I backed away, eager to avoid a beating.

“I don’t like the way you’re playing!” Sal said.

“It’s ok, it’s ok,” Ray insisted.

“It’s not ok.” Sal glared at us. “You’re just hitting him over and over. Some friends you are!”

He grabbed Ray by the arm and pulled him toward the house. Ray moved his feet as fast as he could to keep from dragging. “Ow,” Ray referred to Sal’s grip on his arm. “Ow ow ow!” he cried.

*

I think Ray is doing okay now. He’s out of jail and was working at one of those instant oil change joints. Before I moved away, I saw him there every three thousand miles. He was happy to see me and spoke fondly of the good old days. He wished we were kids again. He used to ask about Matt and Tobin, but those guys haven’t kept in touch. I never asked him about Sal, though it was never far from the tip of my tongue.

*

While we played football in our backyards, there was more to do in the woods. We built fires but quickly put them out before a grownup could get us in trouble. We waded in the creek and caught crayfish in a bucket. We fished for hours without hooking anything but weeds. After rain, we went down mud slides climaxing into the deepest parts of the creek.

We rode our bikes a lot. Sometimes we took the straightest and most direct path so we could build up the highest speed, but sometimes we went out of our way in search of obstacles, which was slower but more challenging. Either way, we always ended up flying down the big dirt hills, slamming the brakes at the bottom so hard that the back tire spun us around and we finished facing the other direction.

Ray was the least stable on a bike. He was able to build up a good pace on the paved streets in our neighborhood, but he didn’t come close to the same speeds in the woods, where he was convinced the trees, logs, and bends were out to get him. Eventually he built enough courage to go down the big hills, but never before coming to a complete stop at the edge, and then inching forward with his feet on the ground before he couldn’t control it anymore and rolled the rest of the way down, pumping the hand brakes as he went. At the bottom he coasted off to the side, and, before coming back up top to join us, paused to catch his breath and calm his beating heart.

The speed bump at the bottom of the hill turned up randomly one day and instantly added another dimension to our shenanigans. I was already going a healthy speed around the bend before even getting to the top of the decline, and by the bottom I went so fast that the wind in my face almost stung. I hit the bump and leaned back, and the bike and I catapulted high into the air before bouncing back to earth. After that it was a wobbly and mildly terrifying twenty feet before I regained control and avoided the patch of trees that were inconveniently too close. Then we all raced back to the paths to build up speed and do it again.

Tobin was the first to lose control. His aim was off and he went over the speed bump too far to the left, where it was uneven. The bike tipped over midair and crashed to the ground on its side. Pinned between the bike and the ground, Tobin slid for several feet before flipping the bike off and hopping up.

“Wow!” he exclaimed. The rough dirt had scraped a good bit of skin off of his legs just below the knee and there was already some blood visible even from the top of the hill. “Man, that hurt!” he said, clearly in pain, but relishing it. He got back on his bike, howled briefly as he pedaled back up top where he bypassed my turn in line, sped down the hill and over the bump, picked up some air, and skidded to a stop a few feet in front of a large tree.

“That was your best one yet!” I called down to him.

“All right, killer,” Matt said to Ray. “You’re up.”

Ray stood with Matt and me at the top and peered down the hill towards the bottom, where a little mound of dirt, a mountain to him, stood in his way.

“I don’t know, guys,” he said, with tiny saliva bubbles collecting at the corners of his mouth. “It’s a little scary looking.”

“It’s not scary,” Matt said, rolling his eyes.

“You don’t have to do it,” I said. “But we’ve all done it like twenty times already. It’s easy.”

“You just saw me fall,” Tobin said. “And I’m fine.” Ray glanced warily at Tobin’s bloody leg. “It doesn’t even hurt,” Tobin insisted.

“Just do it,” Matt said. “Or else you’re a baby.”

“It’s fine, man,” I said. “Go for it. It feels really cool.”

Ray looked down the hill again, and then back at us. He sat on his bike and, with his toes still touching the ground, inched forward, as if to the edge of a skyscraper.

“All right!” Matt said. “Now we have a show!”

And Ray pushed off! It was one of his more daring trips down the hill. He didn’t even try to slow down with his feet, and if he was pumping the hand brakes, I couldn’t tell. It was the most confident I’d ever seen him, or would ever see him again. He looked like he was having fun, like he felt good about himself, as if he fit in.

He may not have been pumping the brakes downhill, but once he reached the bottom he slammed them hard. His body’s momentum pushed him forward and he leaned over the handle bars. The front tire wedged and jammed the bike, and inertia sent Ray through the air and crash-landing shoulder first into the ground.

Ray’s screams were heard throughout the woods. Matt, Tobin, and I were down the hill in seconds. Tobin grabbed ahold of Ray’s arm to help him off the ground, but Ray’s shrieks only grew louder.

“I’ll go get help!” Tobin said with an air of responsibility for his neighbor. He tore off on his bike and out of sight. He couldn’t have been gone more than ninety seconds before Matt and I started wondering what was taking so long.

Ray had a broken collar bone, we would later learn. Matt and I did what we could to console him. We told him that Tobin would be back soon with his parents. We told him a doctor would set everything right. We apologized for making him go down the hill. We told him how brave he’d been, and how good he looked as he approached the bottom. It didn’t matter what we said; the sobs, tears, and mucus kept coming.

Matt couldn’t take it any longer and made up some crap about how Tobin must’ve gotten lost.

“Can you walk?” I asked Ray once Matt had disappeared.

Ray nodded silently and got his feet under him to stand up. I balanced our two bikes on either side of me and, with one hand on each set of handlebars, slowly rolled them up the hill. The pedals banged and scraped against my shins. We walked for ten minutes, Ray’s whimpering and sniffling my only clues to his presence, before we and the bikes emerged from the woods onto the sidewalk along the four lanes.

A familiar car screeched as it pulled to a stop at the side of the road.

“Oh my God, Ray, honey,” Ray’s mother said as she got out of the car and rushed to her son’s side. Ray’s crying had sedated, but he let loose again in his mother’s bosom.

Tobin got out of the car, too, and stood sheepishly by my side. Sal had driven. He popped the trunk and picked up my bike.

“That’s mine,” I said.

He put it back down, glared at me, picked up the other bike, and threw it in the trunk. Ray’s mom helped her son into the back seat of the car and buckled the seatbelt for him.

“See you later, Ray,” I said.

The grown-ups got into the car without saying anything to me. Ray didn’t look up from the back seat. Sal violently glared at us once more before pulling away from the curb, into traffic, and down the road. I still had my bike as Tobin and I began walking home. It was rush hour and the road was loud with speeding cars inches from the sidewalk.

“You all right?” I said to Tobin. He’d been silent since he returned with Ray’s parents. His lips moved but I couldn’t make out any words.

Sal hadn’t said anything but the look he’d given us more than made up for it. I remembered him scolding us once before, and I was sure Tobin was thinking, too: some friends we are.

End

End

A graduate of Florida State University and Roberts Wesleyan College, Joshua Britton has been published in Tethered by Letters, Cobalt Review, Bodega, Steam Ticket, Typehouse Literary, and Spank the Carp. A father of two, Joshua now lives in Evansville, IN, where he is a freelance writer, teacher, and trombonist. Contact Joshua at joshua_britton@yahoo.com.

Leave a Reply