Fiction by D.T. Griffith ‡ Art by Guinotte Wise

The Newsman’s wagon crossed the small city’s limits drawn by two horses, a black mare and her black and white spotted foal, their once silky sheens matted with dried ruddy mud and other debris from the barren land. Not much left to define the limits. A sign read Established in 1763; an intentional array of rusted bullet holes rendered the city nameless some decades ago. Remnants of barricades constructed from damaged cars and sand bags lined the city’s entryways that once housed machine gunners, mortars, and probably a few snipers during the last civil battle. Did anyone even remember those battles, the Newsman wondered. He remembered too well, staying out of battle to report on it as a member of the unbiased press. Not that it matters now; both sides are gone, innocent descendants of survivors sparsely populating what was once a great country. Very few people of his generation still alive outside of Appalachia.

He reached out to drag his hand along the weather-beaten sandbags as the horses followed a wide street to the city center. Brownstones led to taller buildings looming over both sides of the street, some broken, crumbled, and twisted, others still structurally sound and presumably homes to the nomadic families of this region seeking refuge from the hundreds of miles of arid landscape and dried lakebeds. Fires set by the Youth Rising Movement destroyed the last of any forests and charred the landscape decades earlier as rain had ceased to fall over much of the continent as heavy air pollution took its tool.

Most of these people were too young to remember, he figured, as most people his age were detained in camps and then executed by the tens of thousands. The Youth Rising Movement saw their two youngest generations almost completely wiped out by The Elders. These descendants of those who survived, he realized, had no connection to this new world, or the old world of lush green flora and clean water of his youth. Unless they visited Appalachia, which seceded from the country and declared their self an isolationist nation complete with heavily guarded borders. They managed to recycle their water and sustain their lives by agricultural means. A mountain oasis surrounded by deserted urban sprawl, dead barren lands, and a few ghost towns.

The Newsman, as the city’s inhabitants knew him, parked his wagon in the city square along side a splintered wood platform about six feet above the ground where he always set up shop. Within a short time, the people broke from their bazaar of farm stands and textiles to come hear what news he had to deliver.

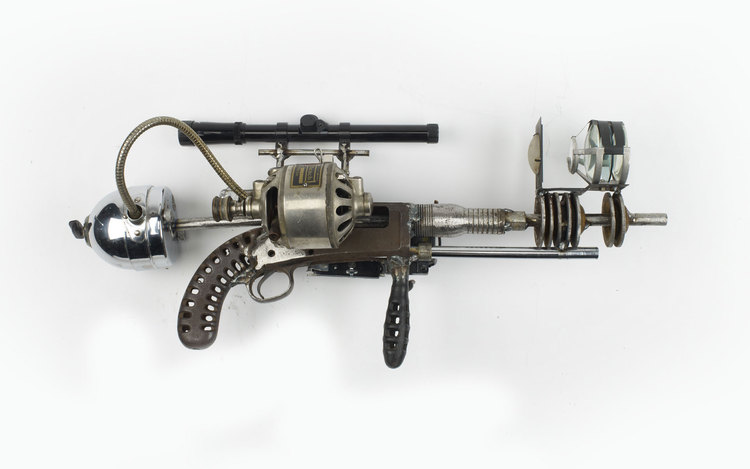

“I come to you with great news,” he shouted digging his hand into a worn nylon backpack spotted with oil stains sitting at his feet, a schoolchild’s relic from his younger days as a fledgling news reporter. “I present you with the power of all power in this new world of desolation and warring tribes. I present you with the last gun.” He paused and watched the faces of the gathering crowd. They gazed at the weapon to no avail. He pushed them further, “this is the last known gun on the continent!”

The old man held what he knew to be a revolver above his head, firmly gripping the partially slick barrel, to the groans of the audience, its luster worn from years of neglect. “I found it in an old friend’s home after he had passed to the great beyond.”

“Whadda joke,” shouted a young blond man with no teeth. “There’s no such thing as da great beyond.” He turned to look at everyone in the small crowd raising his bleach-white arms to hold the crowd’s attention. “We all know guns killed our parents, our grandparents, our world, our homes!”

The small crowd nodded with a verbalized consent of yups and uh-huhs. Then fists appeared in the air one by one. Covered in red dust, some holding produce from the bazaar, some missing fingers, a few stubs ending at the wrist or a partial palm. Pumping in unison as the dissenting voices shouted.

“Death to you, Newsman,” a young dark skinned woman cackled, her long braids whipped back. She grinned and pointed her index finger at him, drawing his eyes to her.

A heavier man with pale-leathered skin, typical of the city-dwellers in the region lacking direct sunlight and water, pounded his fist on the edge of the platform stage. “Screw you, asshole. Guns killed our parents.” He wasn’t the sort of obese person they had seen pictures of in old American books littering the floors of empty storefronts with titles like Us Weekly and People. He stooped low and lobbed a lazy stone at the Newsman’s feet. He coughed as he regained his stance, wet streaks in the red dust on his cheeks streamed from his eyes. “That’s all yo’ gun is worth to us.”

“I have bullets,” the Newsman continued ignoring the impolite audience. He kicked the stone back at the man without giving it any thought. “Two-hundred fifty-six clean bullets.” He held one out between his thumb and forefinger for the crowd to gaze at. “I know they work well, I used two myself.”

“Wha’d you shoot?” taunted a red headed woman. “A pile of rocks?” She laughed, deep leathery creases around her mouth exposing five distorted teeth and blackened gums.

“Two men on the road who tried to take it from me,” he quickly answered. “They should have died by now, bled out from wounds no one knows how to mend anymore.” He continued with a deep rasp in his throat. “I watched them lay there on the dirt and ash, bleeding, screaming and convulsing, begging me for help, for water.” He looked down to his feet and shook his head. “I rode away. I poured a handful of red ash and stones on the wounds and watched them squirm.” He shook his head for effect. “Poor stupid bastards.”

He cleared his throat and wiped his face with a blue bandana.

“I offer them for sale to the highest bidder.”

No one responded. The crowd had grown quiet. The news of a gun used to kill two people in this day was unusual. News of any guns was unusual; they disappeared as The Elders died off. During past visits the Newsman shared stories of hidden mass storage facilities housing all sorts of weaponry left over from the war, but people lost their interest as decades crept into the red ashen soil that had become ubiquitous and water more scarce by the day.

He held the gun toward the sky, “it works, it’s the real thing,” and squeezed the trigger. The metallic click of the revolver’s hammer was audible to crowd. He looked around for any signs of interest. The woman with the braids stepped closer, keeping her smile. He waited, motioning the gun at the audience to gain interest. “Any bidders?” He looked upon the group of filthy faces and bleached skin spots. “Of course not.”

The Newsman cleared his throat to break the silence. “I also bring you a new song. I learned it from the hunters in the mountain commune up yonder. In Appalachia.”

The Newsman cleared his throat to break the silence. “I also bring you a new song. I learned it from the hunters in the mountain commune up yonder. In Appalachia.”

“We don’t need yo’ music, Newsman, or those mountain people’s,” growled a burly black man with a long gray beard. “We have our own now.” A few people voiced their agreement.

The Newsman placed the gun and bullet in the backpack at his feet. He turned to his wagon behind him to reach for an acoustic guitar, strung with gnarly strings he wound over the years from strands of wire he found in a deserted warehouse. The tuning wasn’t great, he knew, but he did his best remembering what recorded songs sounded like from his youth before the now long-dead government had banned them.

The braided woman approached the stage. “Play me a song, Newsman, one of those love ballads.”

“Love ballads?” yelled a voice in the group, “why would ya care about love, whore?”

The Newsman knelt on his good knee and brought his face close to hers. “Good to see you, love.”

“I was wond’ring when we’d see you again. It’s been at least a month and these men ‘round here ain’t got much to offer like you older healthier folk.”

“You’re making me blush, Leana.”

“Yeah, well, play me a love song. The crowd here wants to hear it. They just don’t know it yet. Then maybe you and I … later?” She propped herself on the edge of the stage to the disgruntled tones from the crowd.

“Heh, sure,” he chuckled. “Been a while.” He looked past Leana’s gaze to see the people had grown restless, a few already returning to the bazaar tents.

“I got a song,” he announced, “a song about seeking beauty from long ago, passed down by generations in Appalachia.”

“You mean beauty like that whore sitting next to you?” the fat man shouted and laughed.

“Screw you fat man,” Leana scolded.

“Hey hey hey … take it easy folks, this here song is meant to make you smile. It’s called I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.”

“What the hell is a rainbow,” a voice in the back of crowd asked.

“It’s this uh … phenomenon that occurs when the sunlight hits the rain a certain way,” the Newsman felt compelled to explain.

“Rain?” a few people muttered together. “You’re joking, right?” said the burly man.

“It’s in the old books,” Leana said, “don’t you idiots read? It’s when water falls from the sky.” She held up her hand to create a C-shape between her index finger and thumb, “in little drops about this big.”

“Bullshit from the past,” the burly man said, “ain’t no such thing anymore.”

“You’re an ass,” Leana said, staring him down. “Play yo’ song, Newsman.”

The Newsman strummed his guitar and adjusted the tuning pegs. Not quite right, he remembered, but good enough. He played a simple melody between two strings and sang along.

“My baby can sing better than you and he’s got no tongue,” laughed the red-haired woman.

Leana ignored the hecklers and watched the Newsman perform, smiling and meeting his eyes whenever he looked her direction. She moved her left hand slowly towards the backpack at his feet. With a quick swipe she felt the form of the revolver underneath the nylon fabric. The song ended.

“Oh Newsman, play us some more, something interesting, something about … death.”

“Shut up,” the fat man shouted, taking a few steps towards Leana. “We got no interest in hearing music about death.”

“Why fat man, too scared?”

“No, I ain’t scared of anything, whore.”

“Good. Neither am I.” She turned to look back to the Newsman, standing there with guitar in hand, leaning his backside against the side of his wagon. “I really wanna hear some interesting music from you,” she flicked her tongue between her teeth so only he could see it.

“Well, uh, I heard this song in Appalachia, they call it a murder ballad….”

“Murder ballad,” the red-haired woman yelled, “what kind of sick thing is that?”

“It’s just a kind of old-fashioned song where someone usually dies. I remember they called this one On the Banks of the Old Ohio.” He immediately strummed a rhythm and spoke more so than sang the lyrics at a slow pace. The crowd listened, grumbles and a heckler’s scoff followed by hushing sounds.

Leana crept closer to the backpack, keeping her eyes focused on the crowd around her. She reached her hand inside the bag and wrapped her fingers around the hilt.

The song finished to a few claps and more groans. “Really dark, man,” a voice in the crowd said at the end of the song.

The Newsman turned to look down at Leana to find her standing on the stage next to him, her left hand hidden behind her back.

“What’s in yo’ hand?” asked the red-haired woman.

“You wanna know?” Leana pointed the gun at the crowd, shifting aim between the red-haired woman and the fat man. “Power.”

“No! You don’t want to do that,” the Newsman cautioned dropping his guitar. “Please, let me take that from you.”

“Ah no, that ain’t happening,” she said. “You all worthless pieces of shit are gonna start doing things my way ‘round this city.” She held the gun to the Newsman’s face. “Sorry love, but I gotta do what’s right or this place is done for.”

“Leana, calm down my love, there aren’t any bullets in the chamber. This is pointless.”

“We’ll see about that,” she aimed the gun at the fat man and squeezed the trigger.

An explosive cacophony unlike anything the crowd had ever heard echoed through the square. The horses bucked and ran away pulling the wagon from behind the stage. Everyone within sight had stopped what they were doing and looked for the source of this noise. The fat man dropped, blood seeping from the side of his belly through his shirt. He coughed as he tried to speak. Everyone in the crowd had stepped away from him.

Leana directed the gun toward the crowd. “Scatter!” One by one, the crowd thinned until the fat man was left alone at the foot of the stage compressing his wound with his left hand. He grunted as he grabbed for the edge of the stage with his other, partial hand.

“Well then, Newsman, you lied to us,” she held the warm barrel against his cheek. “What do you say we go back to my place where I deal with liars my way.”

“How’d you know the chamber wasn’t empty,” he asked nervously.

“Read about tricks like this in a book. Make people feel safe and confident then turn-around and kill ‘em if you have to.” She slowly lowered herself to pick up the backpack of bullets holding the gun to his lower abdomen. “News and guns ain’t the only power, Newsman. I’ll show you power.”

“Wait, what if I told you where to find more guns.”

“You said those were rumors.”

“Maybe I lied, a bit.”

“I’m gettin’ real tired of you’re bullshit, Newsman. I got what I need.” She redirected the barrel and pressed it under his chin. He winced. “Let’s call this a breakup.”

“Whoa, no, you don’t want to do this. The people here, they’ll be afraid of you, they’ll try to kill you in your sleep. You need me.”

“Shut up!” She squeezed the trigger and screamed, arching backwards. A shot fired over the Newsman’s shoulder, the sound rang in his ear; he could only hear a ringing tone against a silent backdrop. He looked down. Leanna lay crumpled on the stage, a knife embedded in the middle of her back, blood spilled over the edge of the stage to the dirt below. Her arms and legs squirmed a little, slowing to a stop within the minute.

The fat man stood there, supporting himself against the platform pressing on his wound with one hand. He looked up at the Newsman. “You brought this on yourself and us,” he whispered, choking between syllables.

“What,” he shouted, “can’t hear.” He shook his head clapping his ears. “I can’t hear,” he cried. He dropped to his knees and hugged his guitar.

“And my wife deserved that,” the fat man muttered. He turned and walked back toward the farm stands.

Leave a Reply